Experiments

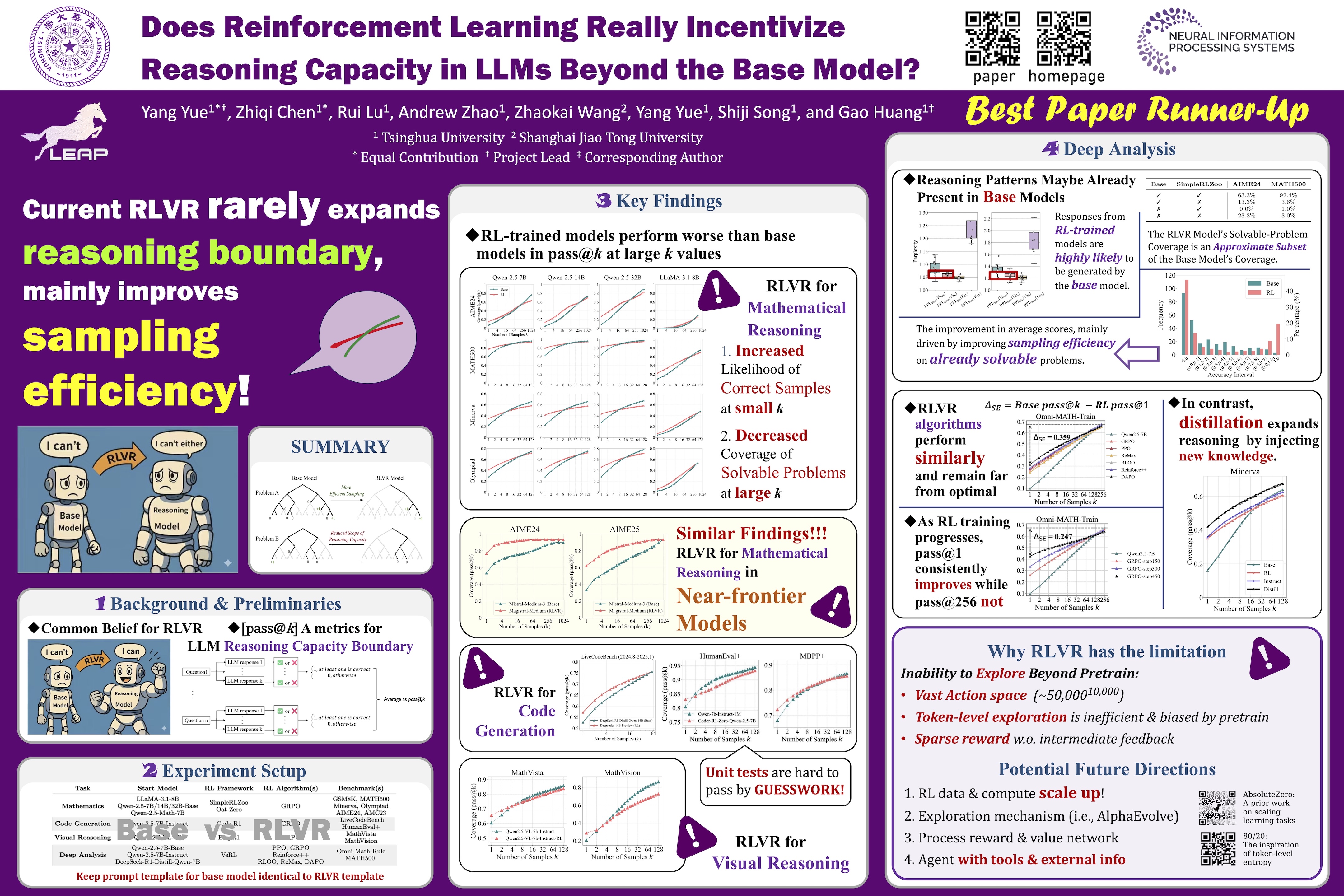

We conducted experiments across three representative domains to evaluate the effect of RLVR on the reasoning ability boundaries of base and RLVR models.

Math

In the math experiments, we evaluate multiple LLM families (Qwen-2.5 and LLaMA-3.1) and their RL-trained variants on benchmarks like GSM8K, MATH500, and AIME24. We analyze pass@k curves to compare base and RL-trained models, observing that RL improves low-k performance but reduces problem coverage at high k. We manually inspect CoT validity to ensure correct answers stem from valid reasoning, not lucky guesses. Additionally, we examine Oat-Zero-trained models and filter guessable problems to focus on challenging cases. The results show base models maintain broader reasoning coverage despite RL's initial accuracy gains.

Coding

In the coding experiments, we evaluate the RLVR-trained model CodeR1-Zero-Qwen2.5-7B, derived from Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct-1M, on benchmarks like LiveCodeBench, HumanEval+, and MBPP+. We assess performance using pass@k metrics, measuring correctness based on predefined test cases. The results show RLVR improves single-sample pass@1 scores but reduces coverage at higher sampling counts (k = 128). The original model exhibits continued potential for improvement with larger k, while RLVR's performance plateaus. This indicates RLVR enhances deterministic accuracy but limits exploration diversity.

Visual Reasoning

In the experiments on visual reasoning, we evaluate Qwen-2.5-VL-7B on filtered visual reasoning benchmarks (MathVista and MathVision), removing multiple-choice questions to focus on robust problem-solving. The improvements from RLVR in visual reasoning align with those seen in math and coding benchmarks, indicating that the original model already covers a broad range of solvable problems, even in multimodal tasks. The consistency across domains suggests that RLVR enhances reasoning capabilities without fundamentally altering the model's problem-solving approach.